The Second Lesson of the Course

Commentary on Chapter 2 of D'Angelo-West Text

24jan11, 21may13, 23may13\begin{document} \maketitle

Summary

In this lesson you will review set theory, and learn the symbolic vocubulary for mathematical statements and proofs. \section{Introduction} Chapter 2 of our textbook is chiefly concerned with mathematical language. More precisely, it lightly treats the notation and application of three areas of logic, \begin{enumerate} \item Set Theory, as in $ A \subset (A \union B) $ and $ A = \{x| x\in A \}$. \\ \item Propositional Logic, as in $ (P \implies Q) \equiv (\neg P \or Q)$. \\ \item Predicate Calculus, as in $ (\forall \epsilon > 0)(\exists \delta > 0) (\forall 0 < x <\delta) (|\frac{\sin(x)}{x} - 1| < \epsilon )$. \\ \end{enumerate}

Quetion1: Prove that$ A \subset (A \union B)$ and $(A \cap B) \subset A$.

Hint: Show that if $x \in LHS$ then $x \in RHS$.

Here is a translation of these symbolic statements in common speech.

\begin{enumerate}

\item The set $A$ is a subset of the union of sets $A$ and $B$.

\item The proposition "$P$ implies $Q$" is equivalent to the

proposition "either the negation of $P$ or $Q$ is true".

\item For all positive numbers $\epsilon$ there exists a positive

$\delta$ such that for all positive $x$ smaller than $\delta$ the

ratio of $\sin(x)$ to $x$ is smaller than $\epsilon$.

\end{enumerate}

Note how common speech is inadequate to express the mathematical statements

without ambiguity. For example, in (2) does "or" mean that

$\neg P$ or $Q$ must be false? Again, in (3), is the $\delta$ the

same for all $\epsilon$? Neither of these is correct.

Question 2 : Use the concept of limit to give another paraphrase of (3).

We'll assume you're familiar with Set Theory and are willing to accept

a slightly more rigorous introduction to \textit{propositional logic}

than Chapter 2 of D'Angelo-West provides. However, you can learn to

use \textit{ quantified propositions} correctly from observation and

practice. A rigororous introduction to this is the subject of a first

course is logic.

\section{Propositional Logic}

To test the validity of compound statements we use the concept of

truth tables. For typographical reasons we refer you to the

LaTeX document on

Truth Tables next. Many LaTeX structures in this

document would be too difficult to reproduce here. Since you will want

to use similar notation, you will find both \texttt{ truth.tex} and

\texttt{truth.pdf} in Advice > LaTeX Sampler. You can download both files.

On a PC you will have to rename \texttt{truth.tex} to \texttt{turth.txt}

before Wordpad will open the file. Note that the only difference between

these two files is the suffix in their names. In most browsers, you

can read \texttt{truth.pdf} by just selecting it (clicking on it).

By the middle of the term you will be able to read (most of) the LaTeX

code in \texttt{truth.tex}. LaTeX is a language you learn by using it.

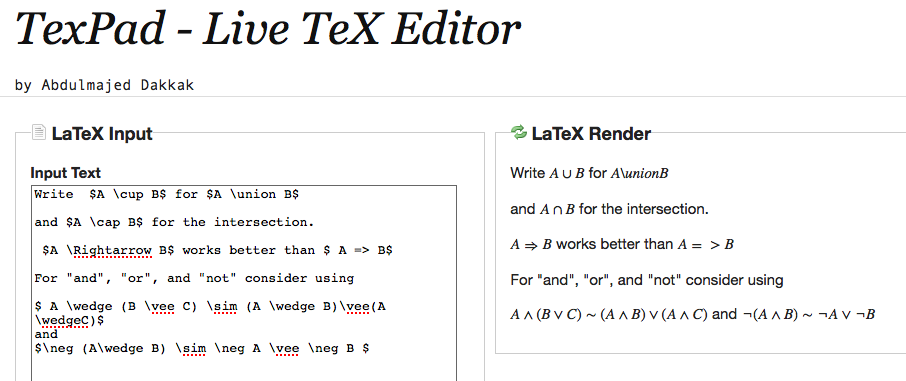

To see what a LaTeX phrase means, and to experiment modifying it, you

can use texPad. But note, if you do use texPad, you may have to use

less mathematical sounding names for the same symbol, for example

"cup" for "union", "Rightarrow" for "implies" etc.

Here is an example created with texPad. The MathML compliant LaTeX

code is on the left, and the symbolic output is on the right.

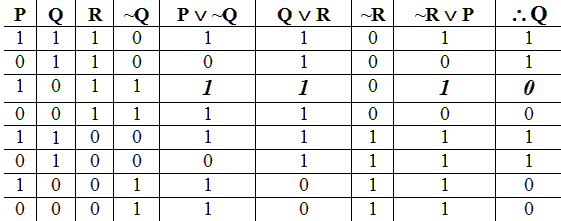

The truthtable in the first illustration at the begining of this

lesson matches most closely the exposition in D'Angelo-West,

except that they use the more anglo-centric letters T and F

for "true" and "false" than our 1 and 0.

Finally, plaintext (e.g. email math) you can improvise some logical symbols.

For "and" you can use the carat ^ symbol, for "or" use a lower case v,

for "implies" use =>. Use the tilde ~ for equivalence $\equiv$. But note

in the illustration that its basic LaTeX name is "sim" for "similar."

Since two compound propositions are equivalent if and only if their

truth values are the same (for given truth values of the component of

the compound), it is not incorrect to use the = sign in plaintext for equivalence.

Thus "(B v notB) = 1" says that whether "B=1" or "B=0", Hamlet's tautology,

"B v notB" is true regardless. Finally, you can always use the LaTe codes

and your mathematal correspondent will understand what you mean.

\section{Filecard Questions}

After you have studied the lesson on truthtables linked to this page, please

answer the following.

less mathematical sounding names for the same symbol, for example

"cup" for "union", "Rightarrow" for "implies" etc.

Here is an example created with texPad. The MathML compliant LaTeX

code is on the left, and the symbolic output is on the right.

The truthtable in the first illustration at the begining of this

lesson matches most closely the exposition in D'Angelo-West,

except that they use the more anglo-centric letters T and F

for "true" and "false" than our 1 and 0.

Finally, plaintext (e.g. email math) you can improvise some logical symbols.

For "and" you can use the carat ^ symbol, for "or" use a lower case v,

for "implies" use =>. Use the tilde ~ for equivalence $\equiv$. But note

in the illustration that its basic LaTeX name is "sim" for "similar."

Since two compound propositions are equivalent if and only if their

truth values are the same (for given truth values of the component of

the compound), it is not incorrect to use the = sign in plaintext for equivalence.

Thus "(B v notB) = 1" says that whether "B=1" or "B=0", Hamlet's tautology,

"B v notB" is true regardless. Finally, you can always use the LaTe codes

and your mathematal correspondent will understand what you mean.

\section{Filecard Questions}

After you have studied the lesson on truthtables linked to this page, please

answer the following.

Question 3: Prove DeMorgan's Law

$ A \wedge (B \vee C)) \sim (A \wedge B)\vee (A \wedge C)$ by considering

truth values.

Question 4: What is $ A \vee (B \wedge C))$ equivalent to?

Question 5: Simplify $ \neg( A \Rightarrow B)$.

Question 6:

Why is the negation of $A \Rightarrow B$ not just $B \implies A$ ?

Question 7: Write "$A$ if and only if $B$" in symbols. Find its truth table.

\end{document}