Z1 revised 20jun11

\section{Introduction}

This lessons reviews the fundamentals of the \textit{complex number field}

and how it describes the geometry of the Cartesian plane.

\section{What you should study now.}

To follow the present introduction to the \textit{complex plane}

you should

\begin{itemize}

\item Study Hvidsten section 4.5, pages 131 and 132.

\item Practice by solving Hvidsten's problems 3.5.1--3.5.5.

\item Study this lesson and submit the filecard questions.

\item Update your journal.

\end{itemize}

\section{Discussion of Euler's Formula}

The best way to relate complex numbers to the Cartesian plane (which is

something you have already learned in calculus) is to remind you that the

\textit{Cartesian form} of a complex number, $ z=x + iy $, is just

a different way of writing a vector with components $(x,y)$. Addition and

subtraction is componentwise, just as with vectors. For $w=(u+iv)$

\[ z \pm w = (x \pm u) + i(y \pm v).\]

\subsection{Complex Multiplication}

Although scalar mutliplication by a real number is also componentwise,

multiplication in general is "different". While

multiplication of complex numbers in Cartesian form is

just a clever application of the venerable \textbf{F.O.I.L. method}

from high school, it is easier to use the polar form.

\[ zw = (x+iy)(u+iv)= xu + iyu + xiv + i^2 yv = (xu-yv)+i(xv+yu). \]

Note that we \textbf{do not} use any symbol to indicate multiplication

of complex numbers.

\section{Introduction}

This lessons reviews the fundamentals of the \textit{complex number field}

and how it describes the geometry of the Cartesian plane.

\section{What you should study now.}

To follow the present introduction to the \textit{complex plane}

you should

\begin{itemize}

\item Study Hvidsten section 4.5, pages 131 and 132.

\item Practice by solving Hvidsten's problems 3.5.1--3.5.5.

\item Study this lesson and submit the filecard questions.

\item Update your journal.

\end{itemize}

\section{Discussion of Euler's Formula}

The best way to relate complex numbers to the Cartesian plane (which is

something you have already learned in calculus) is to remind you that the

\textit{Cartesian form} of a complex number, $ z=x + iy $, is just

a different way of writing a vector with components $(x,y)$. Addition and

subtraction is componentwise, just as with vectors. For $w=(u+iv)$

\[ z \pm w = (x \pm u) + i(y \pm v).\]

\subsection{Complex Multiplication}

Although scalar mutliplication by a real number is also componentwise,

multiplication in general is "different". While

multiplication of complex numbers in Cartesian form is

just a clever application of the venerable \textbf{F.O.I.L. method}

from high school, it is easier to use the polar form.

\[ zw = (x+iy)(u+iv)= xu + iyu + xiv + i^2 yv = (xu-yv)+i(xv+yu). \]

Note that we \textbf{do not} use any symbol to indicate multiplication

of complex numbers.

\textbf{Proof: } For consider where the

unit circle crosses the unit circle about the point 1.

By the Pythagorean theorem, it is at $ \frac{1+i\sqrt{3}}{2 $,

whose \textit{imaginary part} is irrational, hence this

point in the real Cartesian plane is not a point in the rational

Cartesian plane.

This point is missing hence in the rational Cartesian model of Euclid's

Postulates these two circles do \textbf{not} intersect.

\subsection{The surd plane and angle trisection}

On the other hand, recall that we could construct the

\textit{geometric mean} using ruler and compass. Therefore,

we can construct squareroots of by noting that $x = 1 x $,

and so $\sqrt{x} = \mbox{geometric mean}(1,x)$. Suppose

we added a square-root key to our four function calculator and

considered all possible numbers we could calculate just adding,

subtracting, multiplying, dividing and taking square-roots.

These numbers constitute the \textit{field of surd numbers}

which we'll denote by $\Sigma$.

In 1837, Pierre Wantzel finally settled the 2100 year old problem

of trisecting the angle, squaring the circle and doubling the

cube using (unmarked) ruler and compass alone. He showed that

the \textit{surd plane}, $\Sigma + i \Sigma$,

consisting of all points in the plane

both of whose coordinates are surds, is identical with all the

possible points that can be constructed from a unit segment using

only compass and straigthedge. Then he showed the much more difficult

theorem that trisecting certain angles (for instance with a

marked ruler, as Archimedes showed in our first lesson) could

produce an angle, one of whose sides is the real-axis (the

x-axis) and the other side has only non-surds on it (except for

the vertex.) Therefore, this angle could never be constructed by

compass and straightedge alone.

Notice the recurrence of the vulgar distaste for mathematics

which disfigures such legitimate mathematical names as

\begin{itemize}

\item \textit{negative} numbers = $\mathbb{Z} - \mathbb{N} $ \\

\item \textit{irrational} numbers = $\mathbb{R} - \mathbb{Q} $ \\

\item \textit{absurd} numbers = $\mathbb{R} - \Sigma $ \\

\item \textit{imaginary} numbers = $ i\mathbb{R} $ \\

\end{itemize}

to mean something unpleasant in the common language.

\textbf{Proof: } For consider where the

unit circle crosses the unit circle about the point 1.

By the Pythagorean theorem, it is at $ \frac{1+i\sqrt{3}}{2 $,

whose \textit{imaginary part} is irrational, hence this

point in the real Cartesian plane is not a point in the rational

Cartesian plane.

This point is missing hence in the rational Cartesian model of Euclid's

Postulates these two circles do \textbf{not} intersect.

\subsection{The surd plane and angle trisection}

On the other hand, recall that we could construct the

\textit{geometric mean} using ruler and compass. Therefore,

we can construct squareroots of by noting that $x = 1 x $,

and so $\sqrt{x} = \mbox{geometric mean}(1,x)$. Suppose

we added a square-root key to our four function calculator and

considered all possible numbers we could calculate just adding,

subtracting, multiplying, dividing and taking square-roots.

These numbers constitute the \textit{field of surd numbers}

which we'll denote by $\Sigma$.

In 1837, Pierre Wantzel finally settled the 2100 year old problem

of trisecting the angle, squaring the circle and doubling the

cube using (unmarked) ruler and compass alone. He showed that

the \textit{surd plane}, $\Sigma + i \Sigma$,

consisting of all points in the plane

both of whose coordinates are surds, is identical with all the

possible points that can be constructed from a unit segment using

only compass and straigthedge. Then he showed the much more difficult

theorem that trisecting certain angles (for instance with a

marked ruler, as Archimedes showed in our first lesson) could

produce an angle, one of whose sides is the real-axis (the

x-axis) and the other side has only non-surds on it (except for

the vertex.) Therefore, this angle could never be constructed by

compass and straightedge alone.

Notice the recurrence of the vulgar distaste for mathematics

which disfigures such legitimate mathematical names as

\begin{itemize}

\item \textit{negative} numbers = $\mathbb{Z} - \mathbb{N} $ \\

\item \textit{irrational} numbers = $\mathbb{R} - \mathbb{Q} $ \\

\item \textit{absurd} numbers = $\mathbb{R} - \Sigma $ \\

\item \textit{imaginary} numbers = $ i\mathbb{R} $ \\

\end{itemize}

to mean something unpleasant in the common language.

Lesson on the Complex Plane

\textit{$\C$ 2010, Prof. George K. Francis, Mathematics Department, University of Illinois} \begin{document} \maketitle \section{Introduction}

This lessons reviews the fundamentals of the \textit{complex number field}

and how it describes the geometry of the Cartesian plane.

\section{What you should study now.}

To follow the present introduction to the \textit{complex plane}

you should

\begin{itemize}

\item Study Hvidsten section 4.5, pages 131 and 132.

\item Practice by solving Hvidsten's problems 3.5.1--3.5.5.

\item Study this lesson and submit the filecard questions.

\item Update your journal.

\end{itemize}

\section{Discussion of Euler's Formula}

The best way to relate complex numbers to the Cartesian plane (which is

something you have already learned in calculus) is to remind you that the

\textit{Cartesian form} of a complex number, $ z=x + iy $, is just

a different way of writing a vector with components $(x,y)$. Addition and

subtraction is componentwise, just as with vectors. For $w=(u+iv)$

\[ z \pm w = (x \pm u) + i(y \pm v).\]

\subsection{Complex Multiplication}

Although scalar mutliplication by a real number is also componentwise,

multiplication in general is "different". While

multiplication of complex numbers in Cartesian form is

just a clever application of the venerable \textbf{F.O.I.L. method}

from high school, it is easier to use the polar form.

\[ zw = (x+iy)(u+iv)= xu + iyu + xiv + i^2 yv = (xu-yv)+i(xv+yu). \]

Note that we \textbf{do not} use any symbol to indicate multiplication

of complex numbers.

\section{Introduction}

This lessons reviews the fundamentals of the \textit{complex number field}

and how it describes the geometry of the Cartesian plane.

\section{What you should study now.}

To follow the present introduction to the \textit{complex plane}

you should

\begin{itemize}

\item Study Hvidsten section 4.5, pages 131 and 132.

\item Practice by solving Hvidsten's problems 3.5.1--3.5.5.

\item Study this lesson and submit the filecard questions.

\item Update your journal.

\end{itemize}

\section{Discussion of Euler's Formula}

The best way to relate complex numbers to the Cartesian plane (which is

something you have already learned in calculus) is to remind you that the

\textit{Cartesian form} of a complex number, $ z=x + iy $, is just

a different way of writing a vector with components $(x,y)$. Addition and

subtraction is componentwise, just as with vectors. For $w=(u+iv)$

\[ z \pm w = (x \pm u) + i(y \pm v).\]

\subsection{Complex Multiplication}

Although scalar mutliplication by a real number is also componentwise,

multiplication in general is "different". While

multiplication of complex numbers in Cartesian form is

just a clever application of the venerable \textbf{F.O.I.L. method}

from high school, it is easier to use the polar form.

\[ zw = (x+iy)(u+iv)= xu + iyu + xiv + i^2 yv = (xu-yv)+i(xv+yu). \]

Note that we \textbf{do not} use any symbol to indicate multiplication

of complex numbers.

Question 1.

Prove that if multiplication of $w$ by $z$ is "componentwise" then

$z$ must be a real number.

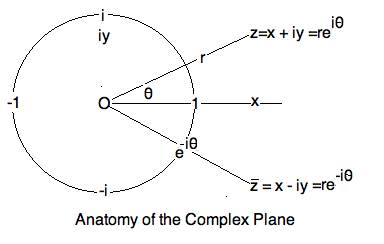

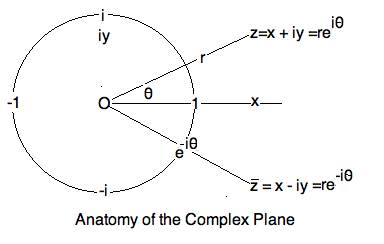

The \textit{polar form} of

a complex number, $z = re^{i\theta}$, expresses a point in the

plane in \textit{polar coordinates}. The point is a distance $r=|z|$ from

the origin, and angle $\theta=\arg(z)$ measured from the x-axis.

Thus the complex numbers $e^{i\theta}$ are exactly the points on the

\textit{unit circle}, which you are used to writing as

$(\cos\theta, \sin\theta)$. Combining these two notions, we get

\textbf{Euler's Formula}.

\begin{eqnarray*}

e^{i\theta} & = & \cos \theta + i\sin\theta \\

\end{eqnarray*}

Question 2.

Use two trigonometric identies and the definition of complex multiplication

in Cartesian form to show that

\[ (re^{i\theta})(se^{i\tau})=rse^{i(\theta + \tau)}. \]

This shows one reason for using the \textit{exponential} notation for the polar

form, the exponents add under multiplication.

Euler had a much better reason for chosing it.

Recall the Taylor series expansion

of the exponential function applied to the term $i\theta$,

then apply the algebraic values of the powers of

$i = \sqrt{-1}$, and finally use the power series for

the sine and cosine functions to obtain this:

\begin{eqnarray*}

e^{i\theta} & = &

1 + i\theta

+ \frac{(i\theta)^2}{2!}

+ \frac{(i\theta)^3}{3!}

+ \frac{(i\theta)^4}{4!}

+ ... \\

&=&

1 + i\theta

+i^2 \frac{\theta^2}{2!}

+i^3 \frac{\theta^3}{3!}

+i^4 \frac{\theta^4}{4!}

+ ... \\

&=&

1 + i\theta

- \frac{\theta^2}{2!}

-i \frac{\theta^3}{3!}

+\frac{\theta^4}{4!}

+i\frac{\theta^5}{5!}

- \frac{\theta^6}{6!}

\pm ... \\

&=&

1 - \frac{\theta^2}{2!}

+\frac{\theta^4}{4!}

- \frac{\theta^6}{6!}

\pm ...

+i\theta

-i \frac{\theta^3}{3!}

+i\frac{\theta^5}{5!}

\pm ... \\

&=& \cos \theta + i\sin\theta \\

\end{eqnarray*}

\section{Rectangular and Polar Coordinates}

Now recall the formulas for changing coordinates in the

plane:

\begin{eqnarray*}

x + iy &=& \sqrt{x^2+y^2}(\frac{x}{\sqrt{x^2+y^2}} +

i\frac{y}{\sqrt{x^2+y^2}})\\

&=& r ( \cos \theta + i\sin\theta) \\

&=& r\cos \theta + i r\sin\theta \\

r &=& \sqrt{x^2+y^2} \\

\theta &=& \tan^{-1}(\frac{y}{x}) \\

x &=& r \cos\theta \\

y &=& r \sin\theta \\

\end{eqnarray*}

Question 3.

Solve $1+i = re^{i\theta}$ for $r, \theta$. Solve $x+iy=2e^{i\pi/3}$ for

$x,y$.

\section{Complex Arithmetic}

The \textit{modulus} of a complex number is its distance from

the origin. Written $ |z| $, it is just the $r$ when $z=re^{i\theta}$

is written in polar form. The angle $\theta$ is called

the \textit{argument} of the complex number $ \arg z $.

Thus, we can dispense with both the Cartesian and polar coordinates

and write

\textbf{Euler's Formula}

\begin{eqnarray*}

z & = & |z| e^{i \arg z } \\

zw & = & |z||w| e^{i (\arg z + \arg w) } \\

\end{eqnarray*}

To be fair to the Cartesian form of a complex number $z=x+iy$,

we have names \textit{ real part, imaginary part} of $z$,

namely $ x = \Re{z}$ and $y = \Im{z}$, so that we can get rid

of $x,y$ too with $ z = \Re(z) + i \Im(z) $.

\section{Rotations and Translations}

With the two equivalent forms of writing complex numbers we

can write the two Euclidean transformations in the plane,

rotation and translation, in a very compact form.

\textbf{Euclidean Transformation Theorem} \\

The \textit{translation} of the entire plane by a vector $m$ takes

every point $z$ to $z + m$. The \textit{rotation} of the

entire plane by an angle $\theta$

about the origin takes every point $z$ to $e^{i\theta} z$.

\textbf{Proof: } \\

Only the second assertion deserves a proof. Note that

\begin{eqnarray*}

e^{i\theta} z &=&

e^{i\theta} |z| e^{i\arg z} \\

&=&

|z| e^{i(\theta + \arg z)} \\

\end{eqnarray*}

which clearly moves $z$ along the circle $ r=|z|$ by an

angle of $\theta$, which is what we claimed.

Question 4.

Show that multiplying a complex number by $i$ the same as rotating about the

origin by $90^o$. Give a geometrical reason that $i^4=1$.

\subsection{Rotation about an arbitrary point.}

If you want to calculate the rotation of the plane about an

arbitrary center $c$, not necessarily the origin, we first

translate the plane so that $c$ moves to the origin, rotate,

and move the plane back by inverse translation. Call this

transformation $f(z)$ and calculate:

\begin{eqnarray*}

f(z)& =& (z - c)e^{i\theta} + c \\

&=& e^{i\theta}z + (1- e^{i\theta})c \\

&=& e^{i\theta}z + f(0) \\

\end{eqnarray*}

\subsection{Complex Conjugate}

The reflection of a point $z$ in the x-axis is called the

\textit{conjugate} of $z$, written

\begin{eqnarray*}

\bar{z} & = & x - iy & = & |z|e^{-i\arg z }. \\

\end{eqnarray*}

It has this important property:

\begin{eqnarray*}

z\bar{z} = (x+iy)(x-iy)=x^2 - (iy)^2 = x^2 + y^2 = |z|^2 \\

\end{eqnarray*}

We can also express the real and imaginary parts of a

complex number thus:

\begin{eqnarray*}

\Re(z) & = & \frac{z + \bar{z}}{2} \\

\Im(z) & = & \frac{z - \bar{z}}{2i} \\

\end{eqnarray*}

You don't need to memorize all these identities, but you do

need to remember the vocabulary so you can re-derive them

when necessary.

Question 5.

Show that if $z=x+iy, w=u+iv$then

$\Re(z\bar{w})=\Re(\bar{z}w)$ gives the \textit{dot product} of these

vectors. Do you recognize what $\Im(z\bar{w})$ evaluates?

\subsection{Complex Inverse}

The multiplicative inverse, or \textit{reciprocal} of a

complex number $z$ can be calculated thus:

\begin{eqnarray*}

\frac{1}{z} =

\frac{\bar{z}}{z\bar{z}} =

\frac{\bar{z}}{|z|^2} \\

\end{eqnarray*}

Hence, we can now \textit{divide} two complex numbers thus:

\begin{eqnarray*}

z/w & = & z\bar{w}/w\bar{w} \\

& = & z\bar{w}/|w|^2 \\

\end{eqnarray*}

\subsection{Field of Complex Numbers}

Recall the definition of a \textit{number field} from MA347 as

a collection of objects closed under two operations, generally

called \textit{addition} and \textit{multiplication}, which

obeys the usual properties of real number arithmetic, in

particular the distributive law and division by non-zero numbers.

Recall too that not only the reals, $\mathbb{R}$, are a field

but also the subset of rational numbers (fractions), $\mathbb{Q}$.

Now you know another field bigger than both, namely the field

of complex numbers, $\mathbb{C}$.

Question 6.

Express $\frac{w}{z}$ in Cartesian and in Polar forms.

\section{Field of Surds}

\subsection{The rational Cartesian plane}

Note that $\mathbb{C}$

contains $\mathbb{R}$ as a subfield, which contains $\mathbb{Q}$

as a subfield. Suppose we consider the subset of points in the

plane both of whose coordinates are rational, call it

$\mathbb{Q} + i\mathbb{Q}$ for short. This too is a field, but

more interesting is the geometry of this socalled \textit{rational

Cartesian plane}. Interpreting points and lines as we did in the case of

Birkhoff's axioms, it is plausible that all five of Euclid's

postulates hold. But already Euclid's first Proposition fails.

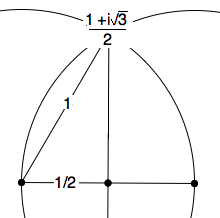

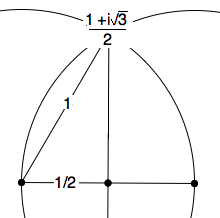

\begin{theorem}

In the rational plane, there is no equilateral triangle with

base of unit length.

\end{theorem}

\textbf{Proof: } For consider where the

unit circle crosses the unit circle about the point 1.

By the Pythagorean theorem, it is at $ \frac{1+i\sqrt{3}}{2 $,

whose \textit{imaginary part} is irrational, hence this

point in the real Cartesian plane is not a point in the rational

Cartesian plane.

This point is missing hence in the rational Cartesian model of Euclid's

Postulates these two circles do \textbf{not} intersect.

\subsection{The surd plane and angle trisection}

On the other hand, recall that we could construct the

\textit{geometric mean} using ruler and compass. Therefore,

we can construct squareroots of by noting that $x = 1 x $,

and so $\sqrt{x} = \mbox{geometric mean}(1,x)$. Suppose

we added a square-root key to our four function calculator and

considered all possible numbers we could calculate just adding,

subtracting, multiplying, dividing and taking square-roots.

These numbers constitute the \textit{field of surd numbers}

which we'll denote by $\Sigma$.

In 1837, Pierre Wantzel finally settled the 2100 year old problem

of trisecting the angle, squaring the circle and doubling the

cube using (unmarked) ruler and compass alone. He showed that

the \textit{surd plane}, $\Sigma + i \Sigma$,

consisting of all points in the plane

both of whose coordinates are surds, is identical with all the

possible points that can be constructed from a unit segment using

only compass and straigthedge. Then he showed the much more difficult

theorem that trisecting certain angles (for instance with a

marked ruler, as Archimedes showed in our first lesson) could

produce an angle, one of whose sides is the real-axis (the

x-axis) and the other side has only non-surds on it (except for

the vertex.) Therefore, this angle could never be constructed by

compass and straightedge alone.

Notice the recurrence of the vulgar distaste for mathematics

which disfigures such legitimate mathematical names as

\begin{itemize}

\item \textit{negative} numbers = $\mathbb{Z} - \mathbb{N} $ \\

\item \textit{irrational} numbers = $\mathbb{R} - \mathbb{Q} $ \\

\item \textit{absurd} numbers = $\mathbb{R} - \Sigma $ \\

\item \textit{imaginary} numbers = $ i\mathbb{R} $ \\

\end{itemize}

to mean something unpleasant in the common language.

\textbf{Proof: } For consider where the

unit circle crosses the unit circle about the point 1.

By the Pythagorean theorem, it is at $ \frac{1+i\sqrt{3}}{2 $,

whose \textit{imaginary part} is irrational, hence this

point in the real Cartesian plane is not a point in the rational

Cartesian plane.

This point is missing hence in the rational Cartesian model of Euclid's

Postulates these two circles do \textbf{not} intersect.

\subsection{The surd plane and angle trisection}

On the other hand, recall that we could construct the

\textit{geometric mean} using ruler and compass. Therefore,

we can construct squareroots of by noting that $x = 1 x $,

and so $\sqrt{x} = \mbox{geometric mean}(1,x)$. Suppose

we added a square-root key to our four function calculator and

considered all possible numbers we could calculate just adding,

subtracting, multiplying, dividing and taking square-roots.

These numbers constitute the \textit{field of surd numbers}

which we'll denote by $\Sigma$.

In 1837, Pierre Wantzel finally settled the 2100 year old problem

of trisecting the angle, squaring the circle and doubling the

cube using (unmarked) ruler and compass alone. He showed that

the \textit{surd plane}, $\Sigma + i \Sigma$,

consisting of all points in the plane

both of whose coordinates are surds, is identical with all the

possible points that can be constructed from a unit segment using

only compass and straigthedge. Then he showed the much more difficult

theorem that trisecting certain angles (for instance with a

marked ruler, as Archimedes showed in our first lesson) could

produce an angle, one of whose sides is the real-axis (the

x-axis) and the other side has only non-surds on it (except for

the vertex.) Therefore, this angle could never be constructed by

compass and straightedge alone.

Notice the recurrence of the vulgar distaste for mathematics

which disfigures such legitimate mathematical names as

\begin{itemize}

\item \textit{negative} numbers = $\mathbb{Z} - \mathbb{N} $ \\

\item \textit{irrational} numbers = $\mathbb{R} - \mathbb{Q} $ \\

\item \textit{absurd} numbers = $\mathbb{R} - \Sigma $ \\

\item \textit{imaginary} numbers = $ i\mathbb{R} $ \\

\end{itemize}

to mean something unpleasant in the common language.