Revised 6may11, 6jun11, 8jun11,14jun11 with thanks to Ki Yeun Kim

And again 22jun11 thanks to Tony Winkler.

\textit{$\C$ 2010, Prof. George K. Francis, Mathematics Department, University of Illinois} \begin{document} \maketitle \section{Introduction} In this lesson we will study Euclid's parallel postulate and its various

equivalent statements. Our exposition is more focussed and somewhat more

rigorous than the exposition in Hvidsten. In particular. we will focus

on an efficient notation, on using the predicate calculus from logic,

as you learned it in MA347, but most of all we will use two particularly

powerful tools. These are first, the Exterior Angle Theorem (XAT) from

absolute geometry, and second, the concept of \textit{Euclid's Line}.

\section{Euclid's Line}

Let us look at Euclid's first postulate more closely. It says two things,

that for any two points there exists a line through them, and that this

line is unique. The uniqueness permits us to invent the notation $(PQ)$

or $\ell_{PQ}$ for \textbf{that} line which joins the two points. Often,

we rename this line by writing $ h =(PQ)$.

What about two lines, what is $(hk)$ ? Suppose the two lines do have

a point in common, $(\exists P)(Ph \and Pk) $. Could there be another?

If there were $Qh \and Qk$ there there would be two lines joining the

same two points, which contradicts Postulate 1. So, if there is such

a point, it is unique, and we write it $(hk)$. If there is no such point,

we have a new word for it, we say the two lines are \textit{parallel}, and

write it as $h \prll k$. We could save ourselves a notation and use

$\neg(hk)$ since it says that there is no common point.

Next, let's have a look at right angles. Postulate 4 is not stated in a

very enlightening way. Whatever Euclid might have meant by it, we know

that that he prized the property of two lines to be \textit{perpendicular},

which we (try) to write as $h \perp k$. We find two propositions

In this lesson we will study Euclid's parallel postulate and its various

equivalent statements. Our exposition is more focussed and somewhat more

rigorous than the exposition in Hvidsten. In particular. we will focus

on an efficient notation, on using the predicate calculus from logic,

as you learned it in MA347, but most of all we will use two particularly

powerful tools. These are first, the Exterior Angle Theorem (XAT) from

absolute geometry, and second, the concept of \textit{Euclid's Line}.

\section{Euclid's Line}

Let us look at Euclid's first postulate more closely. It says two things,

that for any two points there exists a line through them, and that this

line is unique. The uniqueness permits us to invent the notation $(PQ)$

or $\ell_{PQ}$ for \textbf{that} line which joins the two points. Often,

we rename this line by writing $ h =(PQ)$.

What about two lines, what is $(hk)$ ? Suppose the two lines do have

a point in common, $(\exists P)(Ph \and Pk) $. Could there be another?

If there were $Qh \and Qk$ there there would be two lines joining the

same two points, which contradicts Postulate 1. So, if there is such

a point, it is unique, and we write it $(hk)$. If there is no such point,

we have a new word for it, we say the two lines are \textit{parallel}, and

write it as $h \prll k$. We could save ourselves a notation and use

$\neg(hk)$ since it says that there is no common point.

Next, let's have a look at right angles. Postulate 4 is not stated in a

very enlightening way. Whatever Euclid might have meant by it, we know

that that he prized the property of two lines to be \textit{perpendicular},

which we (try) to write as $h \perp k$. We find two propositions

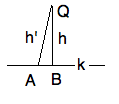

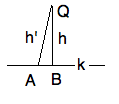

\textbf{Proposition 11} $(Pk) \implies (\exists h)( hP \and h \perp k )$

\textbf{Proposition 12} $\neg(Qk) \implies (\exists h)( hQ \and h \perp k )$

That the perpendicular dropped from a point $Q$ not on a line $k$ is unique

follows from the XAT.

\textbf{Proposition 11} $(Pk) \implies (\exists h)( hP \and h \perp k )$

\textbf{Proposition 12} $\neg(Qk) \implies (\exists h)( hQ \and h \perp k )$

That the perpendicular dropped from a point $Q$ not on a line $k$ is unique

follows from the XAT.

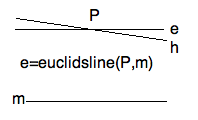

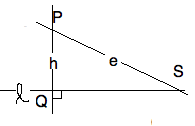

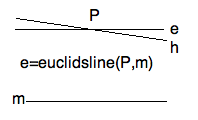

Suppose $\neg P\ell$, we have point not on a line. Drop a perpendicular,

$ hP \and h\perp \ell$, call $Q = (h\ell)$. Now erect the perpendicular,

$ eP \and e \perp (PQ) $. We use the XAT to show that $ e \prll \ell$.

For suppose it intersects $ S=(e\ell)$, then we have a contradiction.

For, the $\angle SPQ $ cannot both be equal to and smaller than a

right angle. Since Euclid's parallel exists and is unique, we shall

use the notation $ e(P,\ell)$. Of course, this notation would not make

sense unless $\neg P\ell$. So, if we say that $ h=e(Q,k)$ we imply

that $Q$ does not line on $k$.

\section{Alternate Interior Angles and all that ... }

Suppose $\neg P\ell$, we have point not on a line. Drop a perpendicular,

$ hP \and h\perp \ell$, call $Q = (h\ell)$. Now erect the perpendicular,

$ eP \and e \perp (PQ) $. We use the XAT to show that $ e \prll \ell$.

For suppose it intersects $ S=(e\ell)$, then we have a contradiction.

For, the $\angle SPQ $ cannot both be equal to and smaller than a

right angle. Since Euclid's parallel exists and is unique, we shall

use the notation $ e(P,\ell)$. Of course, this notation would not make

sense unless $\neg P\ell$. So, if we say that $ h=e(Q,k)$ we imply

that $Q$ does not line on $k$.

\section{Alternate Interior Angles and all that ... }

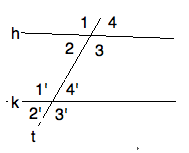

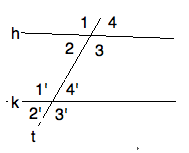

Euclid's fifth postulate is phrased in terms of a \textedit{transversal} line

$t$ to two given lines $h,k$, meaning that $ (ht) \and (kt) $. The figure

immediately produces eight angles. By the \textit{Vertical Angle Theorem}

(Proposition 15) we have that all even pairs are equal, and all odd pairs

are equal. So the real question boils down to whether or not any angle is

equal to it's corresponding (primed) angle, or not. For if one pair of

corresponding angles are equal, all corresponding pairs are. Morever,

adjacent angles are \textit{supplementary}. So another equivalent condition

is for ``interior angles on the same side", $1',2$ for example, are or are

not supplementary. You can amuse yourself by finding all the possible ways

of expressing this condition using ``supplementary" in instead of ``equal".

High school geometry teachers delight in mucking around in this jungle of

possbile ways of saying the ``same thing", and thereby missing the whole

point. (So do college geometry teachers, by the way.)

\textbf{Definition:} We will abbreviate this condition with the

abbreviation $ AIA(t;h,k) $ to mean that the transvserval $t$ of

$h,k$ has any one of the above equivalent angle properties, and read it

as the \textit{Alternate Interior Angle} property for the transversal

$t$ of lines $h,k$. Aren't you glad for notational abbreviations!

The final two theorems of Euclid's absolute geometry, Propositions 27 and

28, just say that $ AIA(t;h,k) \implies h \prll k $.

For, suppose, on the contrary, $\neg h \prll k $, i.e. $ S = (hk)$.

Then $t,h,k$ form a $\triangle HKS$, where $H=(th), K=(tk)$.

The XAT then leads to a contradictions to $AIA(t;h,k)$.

Euclid's fifth postulate is phrased in terms of a \textedit{transversal} line

$t$ to two given lines $h,k$, meaning that $ (ht) \and (kt) $. The figure

immediately produces eight angles. By the \textit{Vertical Angle Theorem}

(Proposition 15) we have that all even pairs are equal, and all odd pairs

are equal. So the real question boils down to whether or not any angle is

equal to it's corresponding (primed) angle, or not. For if one pair of

corresponding angles are equal, all corresponding pairs are. Morever,

adjacent angles are \textit{supplementary}. So another equivalent condition

is for ``interior angles on the same side", $1',2$ for example, are or are

not supplementary. You can amuse yourself by finding all the possible ways

of expressing this condition using ``supplementary" in instead of ``equal".

High school geometry teachers delight in mucking around in this jungle of

possbile ways of saying the ``same thing", and thereby missing the whole

point. (So do college geometry teachers, by the way.)

\textbf{Definition:} We will abbreviate this condition with the

abbreviation $ AIA(t;h,k) $ to mean that the transvserval $t$ of

$h,k$ has any one of the above equivalent angle properties, and read it

as the \textit{Alternate Interior Angle} property for the transversal

$t$ of lines $h,k$. Aren't you glad for notational abbreviations!

The final two theorems of Euclid's absolute geometry, Propositions 27 and

28, just say that $ AIA(t;h,k) \implies h \prll k $.

For, suppose, on the contrary, $\neg h \prll k $, i.e. $ S = (hk)$.

Then $t,h,k$ form a $\triangle HKS$, where $H=(th), K=(tk)$.

The XAT then leads to a contradictions to $AIA(t;h,k)$.

The most popular formulation of Euclid's Parallel Postulate today is due to

Playfair. It says that, through a point $P$ not on a line $m$, $ \neg (Pm)$,

there is exactly one line through $P$ and parallel to $m$, or

\textbf{ Playfair: } $ \neg(Pm) \implies (\exists !\ h)( (Ph) \ \wedge\ h \prll m) .$

But, since we already know that Euclid's parallel $e(P,m)$ exists,

we can reformulate Playfair to:

\textbf{ Playfairer: } $ \neg (Pm) \implies ( (hP) \ \wedge \ h \prll m) \implies h = e(P,m) ) $

Using using the logical equivalence

$ (A \implies (B \implies C)) \equiv ((A \and B) \implies C) $ we can put

Playfair into an a single if-then statement which involves Euclid's parallel.

Indeed, using the generalized Euclid paralell, we can reformulate once

more.

\textbf{ Playfairest: }

$ (\neg (Pm) \and (Mm) \and t=(PM) \and (hP) \and (h \prll m) ) \implies h = e_t(P,m) ). $

\subsection{ Proof that the Euclid5 $\implies$ Playfair.}

So consider $\neg Pf$. Draw any transverse $tP \and (tf)$. By the

contrapositive of the Fifth Postulate, if $hP$ and $ h \prll f$ then

$AIA(t;h,f)$. This says that $h = e_t( P, f)$. In particular for

$t \perp f$, $h = e(P,f)$. So all of these parallels are the

same line, the Euler parallel to $f$ through $P$ .

\subsection{Proof that Playfair $\implies$ Euclid5 }

Given $t,h,k$ with $H=(th)$ and $K = (tk) $. There is always

$e = e_t( K,h)$ which is parallel to $h$. If $h \prll k$ then by

Playfair, $ h= e_t(K,h)$, in other words, $AIA(t;h,k)$. So we

have just proved the contrapositive of Euclid5.

\subsection{The Proof in the Pudding}

For this section you should review your notes for the prerequisites

for this course, for example MA347. In the first section of this course,

on Euclid's Geometry, there is a short remediation which may be adequate

for present purposes.

To show that Euclid's and Playfair's versions said exactly the same thing,

we were obliged to prove what looks like a very complicated theorem of the

form

\begin{eqnarray*}

(H_1 \implies C_1) & \implies & ( H_2 \implies C_2) \\

\end{eqnarray*}

where $H_i$ is the hypothesis, and $C_i$ is the conclusion

of Euclid's ($i=1$) and Playfair ($i=2$).

And, we then proved its converse.

Recall that the following lines are logically equivalent

\begin{eqnarray*}

A \implies (B \implies C) \\

\neg A \ \or \ ( \neg B \or C) \\

(\neg A \ \or \ \neg B ) \or C \\

\neg( A \ \and \ B) \or C \\

( A \and B) \implies C \\

\end{eqnarray*}

Applying this to the triple implication above we followed this

strategy. Keep the $A = (H_1 \implies C_1$ intact, complete with

with its quantifiers. Let $B = H_2$ but establish it first. Label

its geometrical objects and consider them as given. Now find a

situation inside the given geometrical arrangments which $A$ can

be applied to. I.e. replace any fully quantified, so-called dummy

variables in $A$ with the letters from $B$.

\textbf{ Proof Strategy }

\begin{itemize}

\item To show that: if $ H_2 \and (H_1 \implies C_1)$ then $C_2$ holds.

\item Consider $H_2$ as given.

\item Apply $(H_1 \implies C_1)$ to the case of $H_2$.

\item In order to conclude that $C_2$ is true.

\end{itemize}

\subsection{Five Problems on the subject}

To show that you understood the review of prerequisites, solve

\textbf{Problem 0.} Show that $A \implies (B \implies C) $ is not equivalent

to $(A \implies B) \implies C $.

Playfair is equivalent to three more ways of formulating the Parallel Postulate.

\begin{itemize}

\item \textbf{Problem 1.} $ (h \prll k \and t \perp h \and (tk)) \implies t \perp k$.

\item \textbf{Problem 1'.} $ (h \prll k \and t \perp h ) \implies t \perp k$. [This is Hvidsten Exercise 2.1.7 ]

\item \textbf{Problem 2.} $ (h \prll k \ \and \ k \prll \ell) \implies (h = \ell \or h \prll \ell) $. [Hvidsten Exercise 2.1.9 ]

\item \textbf{Problem 3.} $ (h \prll k \ \and \ (th) ) \implies (tk) $. [Hvidsten Exercise 2.1.10.]

\item \textbf{Problem 4.} The exterior angle of a triangle is the sum of the opposite interior angles. [ equivalent to Hvidsten Exercise 2.1.8]

\end{itemize}

Correction: Note there is a small, but important difference between the two

formulations of "Perpl". In Problem 1' no assumption is made that $(tk)$

because that is part of being "perpendicular". In other words

\[ t\perp k \equiv (tk)\wedge \angle(tk)= 90^o.\] It is the second which

is "correct" in the sense of being equivalent to Playfair. The first isn't.

Can you tell which direction of the "if and only if" cannot be proved?

The last is known as the \textit{Euclidean Exterior Angle Theorem } EXAT, which

is, of course, equivalent to the \textit{Euclidean Angle Sum Theorem}

which says that the sum of the (interior) angles of a triangle is $\pi$.

To show that you have understood this lesson, prove that each of the

four propositions are equivalent to Playfair (or any of its formulations).

Note that you have to effectively prove eight triple implications using

the above strategy.

The most popular formulation of Euclid's Parallel Postulate today is due to

Playfair. It says that, through a point $P$ not on a line $m$, $ \neg (Pm)$,

there is exactly one line through $P$ and parallel to $m$, or

\textbf{ Playfair: } $ \neg(Pm) \implies (\exists !\ h)( (Ph) \ \wedge\ h \prll m) .$

But, since we already know that Euclid's parallel $e(P,m)$ exists,

we can reformulate Playfair to:

\textbf{ Playfairer: } $ \neg (Pm) \implies ( (hP) \ \wedge \ h \prll m) \implies h = e(P,m) ) $

Using using the logical equivalence

$ (A \implies (B \implies C)) \equiv ((A \and B) \implies C) $ we can put

Playfair into an a single if-then statement which involves Euclid's parallel.

Indeed, using the generalized Euclid paralell, we can reformulate once

more.

\textbf{ Playfairest: }

$ (\neg (Pm) \and (Mm) \and t=(PM) \and (hP) \and (h \prll m) ) \implies h = e_t(P,m) ). $

\subsection{ Proof that the Euclid5 $\implies$ Playfair.}

So consider $\neg Pf$. Draw any transverse $tP \and (tf)$. By the

contrapositive of the Fifth Postulate, if $hP$ and $ h \prll f$ then

$AIA(t;h,f)$. This says that $h = e_t( P, f)$. In particular for

$t \perp f$, $h = e(P,f)$. So all of these parallels are the

same line, the Euler parallel to $f$ through $P$ .

\subsection{Proof that Playfair $\implies$ Euclid5 }

Given $t,h,k$ with $H=(th)$ and $K = (tk) $. There is always

$e = e_t( K,h)$ which is parallel to $h$. If $h \prll k$ then by

Playfair, $ h= e_t(K,h)$, in other words, $AIA(t;h,k)$. So we

have just proved the contrapositive of Euclid5.

\subsection{The Proof in the Pudding}

For this section you should review your notes for the prerequisites

for this course, for example MA347. In the first section of this course,

on Euclid's Geometry, there is a short remediation which may be adequate

for present purposes.

To show that Euclid's and Playfair's versions said exactly the same thing,

we were obliged to prove what looks like a very complicated theorem of the

form

\begin{eqnarray*}

(H_1 \implies C_1) & \implies & ( H_2 \implies C_2) \\

\end{eqnarray*}

where $H_i$ is the hypothesis, and $C_i$ is the conclusion

of Euclid's ($i=1$) and Playfair ($i=2$).

And, we then proved its converse.

Recall that the following lines are logically equivalent

\begin{eqnarray*}

A \implies (B \implies C) \\

\neg A \ \or \ ( \neg B \or C) \\

(\neg A \ \or \ \neg B ) \or C \\

\neg( A \ \and \ B) \or C \\

( A \and B) \implies C \\

\end{eqnarray*}

Applying this to the triple implication above we followed this

strategy. Keep the $A = (H_1 \implies C_1$ intact, complete with

with its quantifiers. Let $B = H_2$ but establish it first. Label

its geometrical objects and consider them as given. Now find a

situation inside the given geometrical arrangments which $A$ can

be applied to. I.e. replace any fully quantified, so-called dummy

variables in $A$ with the letters from $B$.

\textbf{ Proof Strategy }

\begin{itemize}

\item To show that: if $ H_2 \and (H_1 \implies C_1)$ then $C_2$ holds.

\item Consider $H_2$ as given.

\item Apply $(H_1 \implies C_1)$ to the case of $H_2$.

\item In order to conclude that $C_2$ is true.

\end{itemize}

\subsection{Five Problems on the subject}

To show that you understood the review of prerequisites, solve

\textbf{Problem 0.} Show that $A \implies (B \implies C) $ is not equivalent

to $(A \implies B) \implies C $.

Playfair is equivalent to three more ways of formulating the Parallel Postulate.

\begin{itemize}

\item \textbf{Problem 1.} $ (h \prll k \and t \perp h \and (tk)) \implies t \perp k$.

\item \textbf{Problem 1'.} $ (h \prll k \and t \perp h ) \implies t \perp k$. [This is Hvidsten Exercise 2.1.7 ]

\item \textbf{Problem 2.} $ (h \prll k \ \and \ k \prll \ell) \implies (h = \ell \or h \prll \ell) $. [Hvidsten Exercise 2.1.9 ]

\item \textbf{Problem 3.} $ (h \prll k \ \and \ (th) ) \implies (tk) $. [Hvidsten Exercise 2.1.10.]

\item \textbf{Problem 4.} The exterior angle of a triangle is the sum of the opposite interior angles. [ equivalent to Hvidsten Exercise 2.1.8]

\end{itemize}

Correction: Note there is a small, but important difference between the two

formulations of "Perpl". In Problem 1' no assumption is made that $(tk)$

because that is part of being "perpendicular". In other words

\[ t\perp k \equiv (tk)\wedge \angle(tk)= 90^o.\] It is the second which

is "correct" in the sense of being equivalent to Playfair. The first isn't.

Can you tell which direction of the "if and only if" cannot be proved?

The last is known as the \textit{Euclidean Exterior Angle Theorem } EXAT, which

is, of course, equivalent to the \textit{Euclidean Angle Sum Theorem}

which says that the sum of the (interior) angles of a triangle is $\pi$.

To show that you have understood this lesson, prove that each of the

four propositions are equivalent to Playfair (or any of its formulations).

Note that you have to effectively prove eight triple implications using

the above strategy.

The Parallel Postulate

\textit{$\C$ 2010, Prof. George K. Francis, Mathematics Department, University of Illinois} \begin{document} \maketitle \section{Introduction}

In this lesson we will study Euclid's parallel postulate and its various

equivalent statements. Our exposition is more focussed and somewhat more

rigorous than the exposition in Hvidsten. In particular. we will focus

on an efficient notation, on using the predicate calculus from logic,

as you learned it in MA347, but most of all we will use two particularly

powerful tools. These are first, the Exterior Angle Theorem (XAT) from

absolute geometry, and second, the concept of \textit{Euclid's Line}.

\section{Euclid's Line}

Let us look at Euclid's first postulate more closely. It says two things,

that for any two points there exists a line through them, and that this

line is unique. The uniqueness permits us to invent the notation $(PQ)$

or $\ell_{PQ}$ for \textbf{that} line which joins the two points. Often,

we rename this line by writing $ h =(PQ)$.

What about two lines, what is $(hk)$ ? Suppose the two lines do have

a point in common, $(\exists P)(Ph \and Pk) $. Could there be another?

If there were $Qh \and Qk$ there there would be two lines joining the

same two points, which contradicts Postulate 1. So, if there is such

a point, it is unique, and we write it $(hk)$. If there is no such point,

we have a new word for it, we say the two lines are \textit{parallel}, and

write it as $h \prll k$. We could save ourselves a notation and use

$\neg(hk)$ since it says that there is no common point.

Next, let's have a look at right angles. Postulate 4 is not stated in a

very enlightening way. Whatever Euclid might have meant by it, we know

that that he prized the property of two lines to be \textit{perpendicular},

which we (try) to write as $h \perp k$. We find two propositions

In this lesson we will study Euclid's parallel postulate and its various

equivalent statements. Our exposition is more focussed and somewhat more

rigorous than the exposition in Hvidsten. In particular. we will focus

on an efficient notation, on using the predicate calculus from logic,

as you learned it in MA347, but most of all we will use two particularly

powerful tools. These are first, the Exterior Angle Theorem (XAT) from

absolute geometry, and second, the concept of \textit{Euclid's Line}.

\section{Euclid's Line}

Let us look at Euclid's first postulate more closely. It says two things,

that for any two points there exists a line through them, and that this

line is unique. The uniqueness permits us to invent the notation $(PQ)$

or $\ell_{PQ}$ for \textbf{that} line which joins the two points. Often,

we rename this line by writing $ h =(PQ)$.

What about two lines, what is $(hk)$ ? Suppose the two lines do have

a point in common, $(\exists P)(Ph \and Pk) $. Could there be another?

If there were $Qh \and Qk$ there there would be two lines joining the

same two points, which contradicts Postulate 1. So, if there is such

a point, it is unique, and we write it $(hk)$. If there is no such point,

we have a new word for it, we say the two lines are \textit{parallel}, and

write it as $h \prll k$. We could save ourselves a notation and use

$\neg(hk)$ since it says that there is no common point.

Next, let's have a look at right angles. Postulate 4 is not stated in a

very enlightening way. Whatever Euclid might have meant by it, we know

that that he prized the property of two lines to be \textit{perpendicular},

which we (try) to write as $h \perp k$. We find two propositions

\textbf{Proposition 11} $(Pk) \implies (\exists h)( hP \and h \perp k )$

\textbf{Proposition 12} $\neg(Qk) \implies (\exists h)( hQ \and h \perp k )$

That the perpendicular dropped from a point $Q$ not on a line $k$ is unique

follows from the XAT.

\textbf{Proposition 11} $(Pk) \implies (\exists h)( hP \and h \perp k )$

\textbf{Proposition 12} $\neg(Qk) \implies (\exists h)( hQ \and h \perp k )$

That the perpendicular dropped from a point $Q$ not on a line $k$ is unique

follows from the XAT.

Question 1.

Prove that there cannot be two different lines that are perpendicular to

a given line at a given point on the line. Hint: Here is where you can

use Euclid's 4th Postulate to good effect.

Question 2.

Prove that there cannot be two different lines that are perpendicualr to

a given line from a point outside the line. Hint: Use XAT in your

argument.

\subsection{How to use GEX2.0 to check.}

GEX2.0 has three Euclidean models, and three non-Euclidean (hyperbolic)

models. Often, one need to check wether a particular proposition is

\textbf{Absolute, Euclidean, Hyperbolic}. That is, whether is it true

in a Euclidean model (for example, the "natural" plane you know and love).

Check it in a non-Euclidean model. Here it depends,

some things are easily checked

in the Klein model, others in the Poincare model. And some mathematicians

use the UHP model exclusively. So, if a proposition is true in both

models, then it is a theorem in Absolute geometry.

So, when you investigate the above experimentally, you should do two

experiments. Both of which involve measuring and copying angles. In GEX

you can do this as follows. Be sure you keep track of the orientation of

an angle. $\angle ABC$ and $\angle CBA$ are negatives of each other.

If $\angle ABC$ is acute then GEX will

report the angle measure of $\angle CBA$ between 270 and 359 degrees!

\begin{itemize}

\item To Choose an angle click on the vertices in the correct order.

\item To Mark a chosen angle, click on Angle in the drop-down from the Mark button.

\item To Copy an angle to a given ray, Mark the point as Center, and

\item Chose the ray and click the Rotate button.

\end{itemize}

Five minutes of GEX2.0 experimentation (in the Euclidean plane, of course) will

show you how to do this, and avoid common errors of marking an angle in

the wrong order.

\section{Euclid's Parallel}

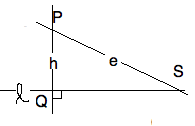

Suppose $\neg P\ell$, we have point not on a line. Drop a perpendicular,

$ hP \and h\perp \ell$, call $Q = (h\ell)$. Now erect the perpendicular,

$ eP \and e \perp (PQ) $. We use the XAT to show that $ e \prll \ell$.

For suppose it intersects $ S=(e\ell)$, then we have a contradiction.

For, the $\angle SPQ $ cannot both be equal to and smaller than a

right angle. Since Euclid's parallel exists and is unique, we shall

use the notation $ e(P,\ell)$. Of course, this notation would not make

sense unless $\neg P\ell$. So, if we say that $ h=e(Q,k)$ we imply

that $Q$ does not line on $k$.

\section{Alternate Interior Angles and all that ... }

Suppose $\neg P\ell$, we have point not on a line. Drop a perpendicular,

$ hP \and h\perp \ell$, call $Q = (h\ell)$. Now erect the perpendicular,

$ eP \and e \perp (PQ) $. We use the XAT to show that $ e \prll \ell$.

For suppose it intersects $ S=(e\ell)$, then we have a contradiction.

For, the $\angle SPQ $ cannot both be equal to and smaller than a

right angle. Since Euclid's parallel exists and is unique, we shall

use the notation $ e(P,\ell)$. Of course, this notation would not make

sense unless $\neg P\ell$. So, if we say that $ h=e(Q,k)$ we imply

that $Q$ does not line on $k$.

\section{Alternate Interior Angles and all that ... }

Euclid's fifth postulate is phrased in terms of a \textedit{transversal} line

$t$ to two given lines $h,k$, meaning that $ (ht) \and (kt) $. The figure

immediately produces eight angles. By the \textit{Vertical Angle Theorem}

(Proposition 15) we have that all even pairs are equal, and all odd pairs

are equal. So the real question boils down to whether or not any angle is

equal to it's corresponding (primed) angle, or not. For if one pair of

corresponding angles are equal, all corresponding pairs are. Morever,

adjacent angles are \textit{supplementary}. So another equivalent condition

is for ``interior angles on the same side", $1',2$ for example, are or are

not supplementary. You can amuse yourself by finding all the possible ways

of expressing this condition using ``supplementary" in instead of ``equal".

High school geometry teachers delight in mucking around in this jungle of

possbile ways of saying the ``same thing", and thereby missing the whole

point. (So do college geometry teachers, by the way.)

\textbf{Definition:} We will abbreviate this condition with the

abbreviation $ AIA(t;h,k) $ to mean that the transvserval $t$ of

$h,k$ has any one of the above equivalent angle properties, and read it

as the \textit{Alternate Interior Angle} property for the transversal

$t$ of lines $h,k$. Aren't you glad for notational abbreviations!

The final two theorems of Euclid's absolute geometry, Propositions 27 and

28, just say that $ AIA(t;h,k) \implies h \prll k $.

For, suppose, on the contrary, $\neg h \prll k $, i.e. $ S = (hk)$.

Then $t,h,k$ form a $\triangle HKS$, where $H=(th), K=(tk)$.

The XAT then leads to a contradictions to $AIA(t;h,k)$.

Euclid's fifth postulate is phrased in terms of a \textedit{transversal} line

$t$ to two given lines $h,k$, meaning that $ (ht) \and (kt) $. The figure

immediately produces eight angles. By the \textit{Vertical Angle Theorem}

(Proposition 15) we have that all even pairs are equal, and all odd pairs

are equal. So the real question boils down to whether or not any angle is

equal to it's corresponding (primed) angle, or not. For if one pair of

corresponding angles are equal, all corresponding pairs are. Morever,

adjacent angles are \textit{supplementary}. So another equivalent condition

is for ``interior angles on the same side", $1',2$ for example, are or are

not supplementary. You can amuse yourself by finding all the possible ways

of expressing this condition using ``supplementary" in instead of ``equal".

High school geometry teachers delight in mucking around in this jungle of

possbile ways of saying the ``same thing", and thereby missing the whole

point. (So do college geometry teachers, by the way.)

\textbf{Definition:} We will abbreviate this condition with the

abbreviation $ AIA(t;h,k) $ to mean that the transvserval $t$ of

$h,k$ has any one of the above equivalent angle properties, and read it

as the \textit{Alternate Interior Angle} property for the transversal

$t$ of lines $h,k$. Aren't you glad for notational abbreviations!

The final two theorems of Euclid's absolute geometry, Propositions 27 and

28, just say that $ AIA(t;h,k) \implies h \prll k $.

For, suppose, on the contrary, $\neg h \prll k $, i.e. $ S = (hk)$.

Then $t,h,k$ form a $\triangle HKS$, where $H=(th), K=(tk)$.

The XAT then leads to a contradictions to $AIA(t;h,k)$.

Question 3.

If $AIA(t;h,k)$ but $S=(hk)$ then which version of AIA is violated?

Refer to the notation $H=(th)$ and $K=(tk)$. Be sure you draw a

figure when you put this into you Journal as well.

Note how similar this argument is to one we used above to establish that

there is only one Euclid's parallel. Here is another proof of the

former using the

uniqueness of the two kinds of perpendiculars. Dropping a perpendicular

from a given point to a given line is unique. Then building a

perpendicular to this new line through the point is also unique.

And that is Euclid's parallel. But read on!

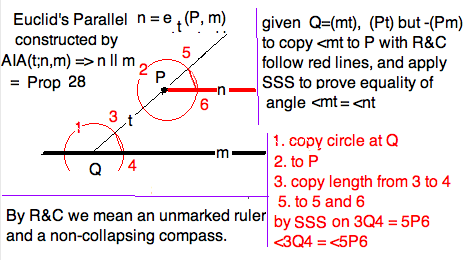

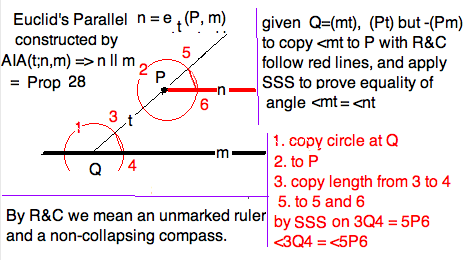

\subsection{High School Construction}

In high school you learned how to

draw parallels by copying angles along any transversal. Given a line $h$

and a point $K$ not on $h$, choose a line $t$ through $H$ that crosses

$h$ at $H$. If you copy the angle $\angle ht$ to $K$ to get $\angle kt$,

then $k \prll h$ because $AIA(t;h,k)$. Since $k$ depends on $t$ we denote

this parallel by $e_t(K,h)$. In high school geometry, given $\neg hK$,

it didn't make any difference which transversal was used, it always

gave the same parallel. But this is not the case in absolute geometry,

because you can show it to be false in a hyperbolic model. (Do it!)

Question 4.

Using any one of the 3 models of hyperbolic geometry in GEX2.0, construct

an example which shows that Euclid's parallel constructed for different

transversal lines from a given point to a given line is not the same.

Then look at the figure in all models. Which is the most convincing?

Submit a .gex file and .png figure with the appropriate homework.

\subsection{Summarizing the above}

A word on notation. The AIA property is an assertion, Euclid's

parallel is a line. The \textit{Altenate Interior Angle} proposition

is a sentence with subject and predicate. Recall, however, all the

other "equal" or "supplementary" angle relations are also asserted

by AIA, since they are all equivalent.

It is

asserted for three given lines. We write $AIA(t;h,k)$. But Euclid's

parallel $e(K,h)$, when the line from $K$ to $h$ is understood to

be the perpendicular, or $e_t(K,h)$ when it is not, is a line. Of

course, the two notations are related.

We have two ways of expressing the same situation

regarding three lines:

\[ AIA(t;h,k) \equiv (k = e_t( (kt), h)) \].

In English, two lines and a transversal for them have the AIA property

if and only if each line is Euclid's parallel to the other relative

to the given transversal. (Aren't you glad we have a notation to

replace such English sentences?)

We proved

\textbf{Proposition 28:} $AIA(t;h,k)\implies h \prll k$,

by applying XAT to its

\textbf{Contrapositive 28:} $ \ \neg h\prllk \implies \neg AIA(t;h,k)$.

Euclid was unable to prove the converse, which says

\textbf{Converse 28:} $ \ h\prllk \implies AIA(t;h,k)$.

But Euclid hoped to be more convincing by

postulating the

\textbf{Inverse 28:} $ \ \neg AIA(t;h,k) \implies \neg h \prllk $,

and this is (very nearly) the statement of his Fifth Postulate.

Euclid also postulates on which side of the transversal the lines meet.

Of course, we already know that the

\textbf{ Negation of Converse 28 :} $(\exists h\ne k)(h \prll k \

\wedge \ (\exists t=trans(h,k))( \negAIA(t;h,k))$

reigns in non-Euclidean geometry.

\section{Playfair}

The most popular formulation of Euclid's Parallel Postulate today is due to

Playfair. It says that, through a point $P$ not on a line $m$, $ \neg (Pm)$,

there is exactly one line through $P$ and parallel to $m$, or

\textbf{ Playfair: } $ \neg(Pm) \implies (\exists !\ h)( (Ph) \ \wedge\ h \prll m) .$

But, since we already know that Euclid's parallel $e(P,m)$ exists,

we can reformulate Playfair to:

\textbf{ Playfairer: } $ \neg (Pm) \implies ( (hP) \ \wedge \ h \prll m) \implies h = e(P,m) ) $

Using using the logical equivalence

$ (A \implies (B \implies C)) \equiv ((A \and B) \implies C) $ we can put

Playfair into an a single if-then statement which involves Euclid's parallel.

Indeed, using the generalized Euclid paralell, we can reformulate once

more.

\textbf{ Playfairest: }

$ (\neg (Pm) \and (Mm) \and t=(PM) \and (hP) \and (h \prll m) ) \implies h = e_t(P,m) ). $

\subsection{ Proof that the Euclid5 $\implies$ Playfair.}

So consider $\neg Pf$. Draw any transverse $tP \and (tf)$. By the

contrapositive of the Fifth Postulate, if $hP$ and $ h \prll f$ then

$AIA(t;h,f)$. This says that $h = e_t( P, f)$. In particular for

$t \perp f$, $h = e(P,f)$. So all of these parallels are the

same line, the Euler parallel to $f$ through $P$ .

\subsection{Proof that Playfair $\implies$ Euclid5 }

Given $t,h,k$ with $H=(th)$ and $K = (tk) $. There is always

$e = e_t( K,h)$ which is parallel to $h$. If $h \prll k$ then by

Playfair, $ h= e_t(K,h)$, in other words, $AIA(t;h,k)$. So we

have just proved the contrapositive of Euclid5.

\subsection{The Proof in the Pudding}

For this section you should review your notes for the prerequisites

for this course, for example MA347. In the first section of this course,

on Euclid's Geometry, there is a short remediation which may be adequate

for present purposes.

To show that Euclid's and Playfair's versions said exactly the same thing,

we were obliged to prove what looks like a very complicated theorem of the

form

\begin{eqnarray*}

(H_1 \implies C_1) & \implies & ( H_2 \implies C_2) \\

\end{eqnarray*}

where $H_i$ is the hypothesis, and $C_i$ is the conclusion

of Euclid's ($i=1$) and Playfair ($i=2$).

And, we then proved its converse.

Recall that the following lines are logically equivalent

\begin{eqnarray*}

A \implies (B \implies C) \\

\neg A \ \or \ ( \neg B \or C) \\

(\neg A \ \or \ \neg B ) \or C \\

\neg( A \ \and \ B) \or C \\

( A \and B) \implies C \\

\end{eqnarray*}

Applying this to the triple implication above we followed this

strategy. Keep the $A = (H_1 \implies C_1$ intact, complete with

with its quantifiers. Let $B = H_2$ but establish it first. Label

its geometrical objects and consider them as given. Now find a

situation inside the given geometrical arrangments which $A$ can

be applied to. I.e. replace any fully quantified, so-called dummy

variables in $A$ with the letters from $B$.

\textbf{ Proof Strategy }

\begin{itemize}

\item To show that: if $ H_2 \and (H_1 \implies C_1)$ then $C_2$ holds.

\item Consider $H_2$ as given.

\item Apply $(H_1 \implies C_1)$ to the case of $H_2$.

\item In order to conclude that $C_2$ is true.

\end{itemize}

\subsection{Five Problems on the subject}

To show that you understood the review of prerequisites, solve

\textbf{Problem 0.} Show that $A \implies (B \implies C) $ is not equivalent

to $(A \implies B) \implies C $.

Playfair is equivalent to three more ways of formulating the Parallel Postulate.

\begin{itemize}

\item \textbf{Problem 1.} $ (h \prll k \and t \perp h \and (tk)) \implies t \perp k$.

\item \textbf{Problem 1'.} $ (h \prll k \and t \perp h ) \implies t \perp k$. [This is Hvidsten Exercise 2.1.7 ]

\item \textbf{Problem 2.} $ (h \prll k \ \and \ k \prll \ell) \implies (h = \ell \or h \prll \ell) $. [Hvidsten Exercise 2.1.9 ]

\item \textbf{Problem 3.} $ (h \prll k \ \and \ (th) ) \implies (tk) $. [Hvidsten Exercise 2.1.10.]

\item \textbf{Problem 4.} The exterior angle of a triangle is the sum of the opposite interior angles. [ equivalent to Hvidsten Exercise 2.1.8]

\end{itemize}

Correction: Note there is a small, but important difference between the two

formulations of "Perpl". In Problem 1' no assumption is made that $(tk)$

because that is part of being "perpendicular". In other words

\[ t\perp k \equiv (tk)\wedge \angle(tk)= 90^o.\] It is the second which

is "correct" in the sense of being equivalent to Playfair. The first isn't.

Can you tell which direction of the "if and only if" cannot be proved?

The last is known as the \textit{Euclidean Exterior Angle Theorem } EXAT, which

is, of course, equivalent to the \textit{Euclidean Angle Sum Theorem}

which says that the sum of the (interior) angles of a triangle is $\pi$.

To show that you have understood this lesson, prove that each of the

four propositions are equivalent to Playfair (or any of its formulations).

Note that you have to effectively prove eight triple implications using

the above strategy.

The most popular formulation of Euclid's Parallel Postulate today is due to

Playfair. It says that, through a point $P$ not on a line $m$, $ \neg (Pm)$,

there is exactly one line through $P$ and parallel to $m$, or

\textbf{ Playfair: } $ \neg(Pm) \implies (\exists !\ h)( (Ph) \ \wedge\ h \prll m) .$

But, since we already know that Euclid's parallel $e(P,m)$ exists,

we can reformulate Playfair to:

\textbf{ Playfairer: } $ \neg (Pm) \implies ( (hP) \ \wedge \ h \prll m) \implies h = e(P,m) ) $

Using using the logical equivalence

$ (A \implies (B \implies C)) \equiv ((A \and B) \implies C) $ we can put

Playfair into an a single if-then statement which involves Euclid's parallel.

Indeed, using the generalized Euclid paralell, we can reformulate once

more.

\textbf{ Playfairest: }

$ (\neg (Pm) \and (Mm) \and t=(PM) \and (hP) \and (h \prll m) ) \implies h = e_t(P,m) ). $

\subsection{ Proof that the Euclid5 $\implies$ Playfair.}

So consider $\neg Pf$. Draw any transverse $tP \and (tf)$. By the

contrapositive of the Fifth Postulate, if $hP$ and $ h \prll f$ then

$AIA(t;h,f)$. This says that $h = e_t( P, f)$. In particular for

$t \perp f$, $h = e(P,f)$. So all of these parallels are the

same line, the Euler parallel to $f$ through $P$ .

\subsection{Proof that Playfair $\implies$ Euclid5 }

Given $t,h,k$ with $H=(th)$ and $K = (tk) $. There is always

$e = e_t( K,h)$ which is parallel to $h$. If $h \prll k$ then by

Playfair, $ h= e_t(K,h)$, in other words, $AIA(t;h,k)$. So we

have just proved the contrapositive of Euclid5.

\subsection{The Proof in the Pudding}

For this section you should review your notes for the prerequisites

for this course, for example MA347. In the first section of this course,

on Euclid's Geometry, there is a short remediation which may be adequate

for present purposes.

To show that Euclid's and Playfair's versions said exactly the same thing,

we were obliged to prove what looks like a very complicated theorem of the

form

\begin{eqnarray*}

(H_1 \implies C_1) & \implies & ( H_2 \implies C_2) \\

\end{eqnarray*}

where $H_i$ is the hypothesis, and $C_i$ is the conclusion

of Euclid's ($i=1$) and Playfair ($i=2$).

And, we then proved its converse.

Recall that the following lines are logically equivalent

\begin{eqnarray*}

A \implies (B \implies C) \\

\neg A \ \or \ ( \neg B \or C) \\

(\neg A \ \or \ \neg B ) \or C \\

\neg( A \ \and \ B) \or C \\

( A \and B) \implies C \\

\end{eqnarray*}

Applying this to the triple implication above we followed this

strategy. Keep the $A = (H_1 \implies C_1$ intact, complete with

with its quantifiers. Let $B = H_2$ but establish it first. Label

its geometrical objects and consider them as given. Now find a

situation inside the given geometrical arrangments which $A$ can

be applied to. I.e. replace any fully quantified, so-called dummy

variables in $A$ with the letters from $B$.

\textbf{ Proof Strategy }

\begin{itemize}

\item To show that: if $ H_2 \and (H_1 \implies C_1)$ then $C_2$ holds.

\item Consider $H_2$ as given.

\item Apply $(H_1 \implies C_1)$ to the case of $H_2$.

\item In order to conclude that $C_2$ is true.

\end{itemize}

\subsection{Five Problems on the subject}

To show that you understood the review of prerequisites, solve

\textbf{Problem 0.} Show that $A \implies (B \implies C) $ is not equivalent

to $(A \implies B) \implies C $.

Playfair is equivalent to three more ways of formulating the Parallel Postulate.

\begin{itemize}

\item \textbf{Problem 1.} $ (h \prll k \and t \perp h \and (tk)) \implies t \perp k$.

\item \textbf{Problem 1'.} $ (h \prll k \and t \perp h ) \implies t \perp k$. [This is Hvidsten Exercise 2.1.7 ]

\item \textbf{Problem 2.} $ (h \prll k \ \and \ k \prll \ell) \implies (h = \ell \or h \prll \ell) $. [Hvidsten Exercise 2.1.9 ]

\item \textbf{Problem 3.} $ (h \prll k \ \and \ (th) ) \implies (tk) $. [Hvidsten Exercise 2.1.10.]

\item \textbf{Problem 4.} The exterior angle of a triangle is the sum of the opposite interior angles. [ equivalent to Hvidsten Exercise 2.1.8]

\end{itemize}

Correction: Note there is a small, but important difference between the two

formulations of "Perpl". In Problem 1' no assumption is made that $(tk)$

because that is part of being "perpendicular". In other words

\[ t\perp k \equiv (tk)\wedge \angle(tk)= 90^o.\] It is the second which

is "correct" in the sense of being equivalent to Playfair. The first isn't.

Can you tell which direction of the "if and only if" cannot be proved?

The last is known as the \textit{Euclidean Exterior Angle Theorem } EXAT, which

is, of course, equivalent to the \textit{Euclidean Angle Sum Theorem}

which says that the sum of the (interior) angles of a triangle is $\pi$.

To show that you have understood this lesson, prove that each of the

four propositions are equivalent to Playfair (or any of its formulations).

Note that you have to effectively prove eight triple implications using

the above strategy.