Similarity and the simSAS Axiom

\textit{$\C$ 2010, 2011, Prof. George K. Francis, Mathematics Department, University of Illinois} \begin{document} 28feb11 \maketitle

\section{Introduction}

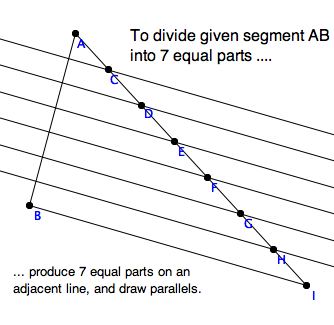

One of the most useful construction you (should have) learned in high school

geometry is to divide a given segment $AB$ into an arbitrary

number, $n$, of equal parts.

You drew a ray from one endpoint, and marked off $n$ equal parts along the

ray, with your compass, or a strip of paper with a mark on it. Say the last

point is $N$. Then the parallels to $\ell_{BN}$ through the points cut $AB$

into $n$ equal parts.

Later, certainly by \textit{Algebra II}, you learned that all real numbers

can be approximated by rational numbers to an arbitrary degree of accuracy.

So, the question is whether you can construct an arbitrary fraction,

$\frac{n}{d}$ of a

given segment. And now you know the answer is yes. You multiply a given

segment the numerator number of times by producing the segment. You divide

the result into the denominator number of equal segments by drawing parallels.

This concept will be made extraordinarily precise in Birkhoff's \textit{Ruler

Axiom}.

\section{Definition of Similarity}

We shall say two triangles are \textit{similar}, $\triangle ABC \sim \triangle A'B'C' $,

if the angles are pairwise equal and corresponding sides have the same

ratio: $ |AB|/|A'B'| =|BC|/|B'C'| =|CA|/|C'A'|$.

\section{Segment division is Euclidean}

This construction is definitely Euclidean.

\section{Introduction}

One of the most useful construction you (should have) learned in high school

geometry is to divide a given segment $AB$ into an arbitrary

number, $n$, of equal parts.

You drew a ray from one endpoint, and marked off $n$ equal parts along the

ray, with your compass, or a strip of paper with a mark on it. Say the last

point is $N$. Then the parallels to $\ell_{BN}$ through the points cut $AB$

into $n$ equal parts.

Later, certainly by \textit{Algebra II}, you learned that all real numbers

can be approximated by rational numbers to an arbitrary degree of accuracy.

So, the question is whether you can construct an arbitrary fraction,

$\frac{n}{d}$ of a

given segment. And now you know the answer is yes. You multiply a given

segment the numerator number of times by producing the segment. You divide

the result into the denominator number of equal segments by drawing parallels.

This concept will be made extraordinarily precise in Birkhoff's \textit{Ruler

Axiom}.

\section{Definition of Similarity}

We shall say two triangles are \textit{similar}, $\triangle ABC \sim \triangle A'B'C' $,

if the angles are pairwise equal and corresponding sides have the same

ratio: $ |AB|/|A'B'| =|BC|/|B'C'| =|CA|/|C'A'|$.

\section{Segment division is Euclidean}

This construction is definitely Euclidean.

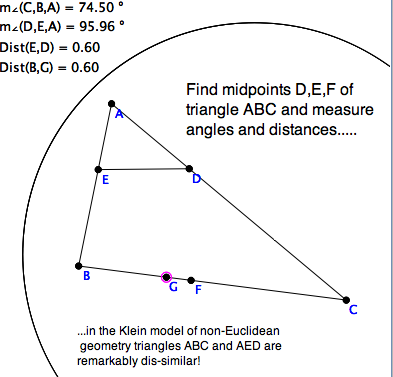

Do the following experiment in the Klein model of hyperbolic

(a.k.a. non-Euclidean) geometry. Bisect the sides of $\triangle ABC$ and

connect the midpoints of sides $b, c$. In Euclidean geometry, this line

should be parallel to the base and half its length. Measure a pair of

corresponding angles, and note they are not equal. The two triangles are

not similar. Moreover, attach a movable point $G$ to the base, and wiggle it

until $|DE|=|AG|$. Note that you cannot make $G=F$, the midpoint of the base.

So, we conjecture from our experiment, that similarity is not part of

lbsolute Geometry, it must be Euclidean.

\section{AAA criterion for Similarity}

In high school geometry, you learned that SAS, ASA, and SSS are criteria

for two triangles to be congruent. You also learned that AAA guarantees

only similarity, not congruence. Let's see how this AAA theorem reduces

to proving the following lemma:

\subsection{Ladder Lemma}

\textbf{Lemma:}

Do the following experiment in the Klein model of hyperbolic

(a.k.a. non-Euclidean) geometry. Bisect the sides of $\triangle ABC$ and

connect the midpoints of sides $b, c$. In Euclidean geometry, this line

should be parallel to the base and half its length. Measure a pair of

corresponding angles, and note they are not equal. The two triangles are

not similar. Moreover, attach a movable point $G$ to the base, and wiggle it

until $|DE|=|AG|$. Note that you cannot make $G=F$, the midpoint of the base.

So, we conjecture from our experiment, that similarity is not part of

lbsolute Geometry, it must be Euclidean.

\section{AAA criterion for Similarity}

In high school geometry, you learned that SAS, ASA, and SSS are criteria

for two triangles to be congruent. You also learned that AAA guarantees

only similarity, not congruence. Let's see how this AAA theorem reduces

to proving the following lemma:

\subsection{Ladder Lemma}

\textbf{Lemma:}

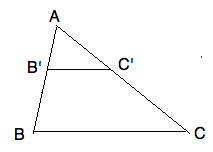

If, in a $\triangle ABC$ chord $B'C'$ is drawn parallel to

base $BC$ then $\triangle ABC \sim \triangle AB'C'$. In particular

$|AB'|/|AB| =|AC'|/|AC| =|B'C'|/|BC|$.

\textbf{Proof:} We will prove the Ladder Lemma later. Here we prove instead

that

\textbf{Corollary:}

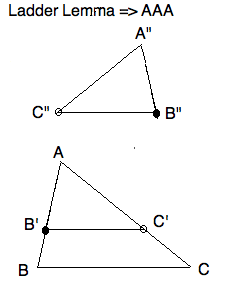

The Ladder Lemma implies AAA is true in Absolute Geometry.

\textbf{Proof of the Corollary.}

So, suppose triangles $\triangle ABC $

and $\triangle A"B"C"$ have correspondingly labeled angles equal. If

a pair of sides are equal, say $|AB|=|A"B"|$ then we have ASA and the

two triangles are congruent. So the side ratio is 1:1 all around. ASA

is a theorem in Absolute Geometry.

Next, suppose that $|AB| > |A"B"|$, then we can lay off $B'$ on $AB$ so that

$|A"B"| = |AB'|$. This is a theorem in Absolute Geometry.

If, in a $\triangle ABC$ chord $B'C'$ is drawn parallel to

base $BC$ then $\triangle ABC \sim \triangle AB'C'$. In particular

$|AB'|/|AB| =|AC'|/|AC| =|B'C'|/|BC|$.

\textbf{Proof:} We will prove the Ladder Lemma later. Here we prove instead

that

\textbf{Corollary:}

The Ladder Lemma implies AAA is true in Absolute Geometry.

\textbf{Proof of the Corollary.}

So, suppose triangles $\triangle ABC $

and $\triangle A"B"C"$ have correspondingly labeled angles equal. If

a pair of sides are equal, say $|AB|=|A"B"|$ then we have ASA and the

two triangles are congruent. So the side ratio is 1:1 all around. ASA

is a theorem in Absolute Geometry.

Next, suppose that $|AB| > |A"B"|$, then we can lay off $B'$ on $AB$ so that

$|A"B"| = |AB'|$. This is a theorem in Absolute Geometry.

Question 1: Locate and identify which of Euclid's propositions says you

can do this.

By assumption, $\angle A = \angle A"$, so we can reconstruct

$\triangle A"B"C"$ at $\triangle AB'C'$ where $C'$ lies on $(AC)$

somewhere. You can't assume anything about where on the ray $AC$ the

point $C'$ is located. For now, put it between $A$ and $C$. But

later, redraw a figure where $C$ is between $A$ and $C'$ and check that

our argument is still valid.

By assumption, $\angle C'B'A = \angle CBA $. Therefore by Proposition

28, $ \ell_{BC} \prll \ell_{B'C'}$. And we have reached the situation

given in the \textit{Ladder Lemma.}

\section{The simSAS Axiom}

Since we have experimental evidence that the Ladder Lemma is false in

non-Euclidean geometry, the Ladder Lemma must have a strong Euclidean

component. In other words, its proof must require a

consequence of Euclid's Parallel Postulate. The proof of the

Ladder Lemma is actually quite difficult. And long ago geometers noticed

that a generalization of SAS to similar triangles was extremely versatile

for proving all sorts of theorems in Euclidean geometry, including

the Ladder Lemma.

\textbf{Axiom simSAS} \\

\textit{For two triangles, if two pairs of sides have the same ratio,

and the included angles are equal, then the triangles are similar.}

Note that Euclid's Proposition 4 (SAS) is a special case, the ratio in

question is 1:1. In fact, simSAS is so versatile, that George Birkhoff

adopted it as one of his only four axioms for Euclidean geometry.

\subsection{The Ladder Lemma follows from simSAS}

We must start with the hypotheses of the Ladder Lemma. To use simSAS, we

must also insure that the hypotheses of simSAS are indeed satified. So

we have some work to do. The included angles, being the same, are equal.

One pair of sides simply has a particular ratio, $|AB'|/|AB|$. To show

that the other ratio, $|AC'|/|AC|$ is the same, we could assume it is different,

and aim for a contradiction. Let's be clever. Let's simply not draw the

rung of the ladder at first, and place $C'$ so that the ratio is the same on

right as on the left. The simSAS says the two triangles are similar. In

particular $\angle AC'B' = \angle ACB$. But then, by the "alternate

interior angle" (AIA) version of Proposition 28,

$\ell_{B'C'} \prll \ell_{BC}$. Now we (finally) use the Parallel Postulate,

in Playfair's form, and see that the rung of the ladder we originally drew

parallel to the base, and the rung of the ladder we constructed to fulfill

the hypotheses of simSAS must be one and the same. And we've proved the

Lemma.

By assumption, $\angle C'B'A = \angle CBA $. Therefore by Proposition

28, $ \ell_{BC} \prll \ell_{B'C'}$. And we have reached the situation

given in the \textit{Ladder Lemma.}

\section{The simSAS Axiom}

Since we have experimental evidence that the Ladder Lemma is false in

non-Euclidean geometry, the Ladder Lemma must have a strong Euclidean

component. In other words, its proof must require a

consequence of Euclid's Parallel Postulate. The proof of the

Ladder Lemma is actually quite difficult. And long ago geometers noticed

that a generalization of SAS to similar triangles was extremely versatile

for proving all sorts of theorems in Euclidean geometry, including

the Ladder Lemma.

\textbf{Axiom simSAS} \\

\textit{For two triangles, if two pairs of sides have the same ratio,

and the included angles are equal, then the triangles are similar.}

Note that Euclid's Proposition 4 (SAS) is a special case, the ratio in

question is 1:1. In fact, simSAS is so versatile, that George Birkhoff

adopted it as one of his only four axioms for Euclidean geometry.

\subsection{The Ladder Lemma follows from simSAS}

We must start with the hypotheses of the Ladder Lemma. To use simSAS, we

must also insure that the hypotheses of simSAS are indeed satified. So

we have some work to do. The included angles, being the same, are equal.

One pair of sides simply has a particular ratio, $|AB'|/|AB|$. To show

that the other ratio, $|AC'|/|AC|$ is the same, we could assume it is different,

and aim for a contradiction. Let's be clever. Let's simply not draw the

rung of the ladder at first, and place $C'$ so that the ratio is the same on

right as on the left. The simSAS says the two triangles are similar. In

particular $\angle AC'B' = \angle ACB$. But then, by the "alternate

interior angle" (AIA) version of Proposition 28,

$\ell_{B'C'} \prll \ell_{BC}$. Now we (finally) use the Parallel Postulate,

in Playfair's form, and see that the rung of the ladder we originally drew

parallel to the base, and the rung of the ladder we constructed to fulfill

the hypotheses of simSAS must be one and the same. And we've proved the

Lemma.

Question 2: Have you understood this proof and put it into your Journal?

\subsection{Exercises}

I hope the above argument has raised your suspicions that somehow Playfair

was really necessary here. Indeed, simSAS must be false in non-Euclidean

geometry. It's actually much worse than you think. It cannot even be stated

in non-Euclidean terms, since there are no similar triangles that are not

also congruent. So only the SAS form of simSAS makes sense there. We

shall not prove that here. Try to locate a proof on the web. There is one

in Hvidsten.

Question 3: Have you found proofs of SAS in Cartesian geometry and put

them into your Journal?