+++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Two non-parallel planes meet along a line. Two parallel planes now meet

along their common ideal line. A plane and a line (that does not

lie in the plane) must meet, either where the line pierces the plane.

Or, if the line is parallel to the plane, they meet "at infinity", i.e.

the ideal point of the line lies on the ideal line on the plane.

Two lines, however, need not meet at all, either at any real point

or at any ideal point. Such lines are called 'skew'.

Can you figure out what it means for a real and an ideal line

to be skew?

pass:[

]

Kepler's peculiar geometry had already been discovered,

practically speaking, by the Rennaissance artists in

their study of perspective. The 'horizon',

particularly familiar for residents of Illinois, is an ideal line. In

perspective, the horizon is drawn as a line in the painter's canvas.

Later, these ideas were adopted by mathematicians as

'projective geometry'. It differs from the traditional Euclidean

geometry in many ways. Most notably, there is greater logical

symmetry between points and lines.

In projective geometry, any two points are joined by a line ( as they

do in Euclid's geometry)

and any two lines (in a plane) have a point in common (non-Euclidean).

In projective 3-space, any two points are joined by a line (Euclidean),

and any two planes meet along line (non-Euclidean).

To exercise this expanded way of thinking we re-examine Desargues'

theorem, but allowing for certain points to be ideal.

Desargues Theorem

-----------------

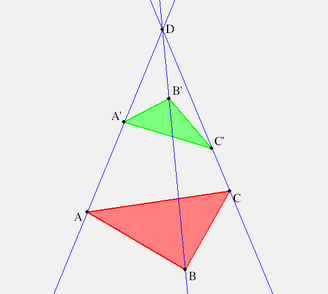

The figure we usually draw to illustrate Desargues Theorem looks

like the following. But you should experiment with figures where

the red and green triangles are in more general positions along the

three lines.

[frame="none",cols="^",valign="middle",grid="all"]

|===================

|pass:[

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Consider four points pass:[$ W = (AC)(BD), X=(AB)(DE), Y=(BC)(EF),

Z = (CD)(FA) $]. The theorem says that if pass:[$ W, X, Y $] are

ideal, then pass:[$ Z $] must also be ideal. In particular,

pass:[$ (XYZ) = \infty $].

pass:[

]

.Exercise.

==================

Use KSEG or ruler and compass to investigate the case that

pass:[$ W $] is a real point. Is it still true? If both pass:[$ X, Y $]

be real too, is it still true that pass:[$ (XYZ) $].

==================

Pascal's Theorem in KSEG

------------------------

Having extended the concept of 'collinearity' to include ideal and

real points in the plane, you should revisit Pascal's generalization of

Pappus' theorem we mentioned earlier. Pascal was so amazed by the

result he discovered, he gave it a fancy name:

[frame="none",cols="^",valign="middle",grid="all"]

|===================

|pass:[ ]

|*Click image to view desargues1.seg with KSEG.*

|

|===================

.Desargues Theorem.

*************

For △asciimath:[ABC] and △asciimath:[A'B'C'] and asciimath:[D=(A A')(B B')(C C')] we have that asciimath:[C^{**}=(A'B')(AB), B^{**}=(C'A')(CA)], and asciimath:[A^{**}=(B'C')(BC)] are collinear, i.e. asciimath:[(A^{**}B^{**}C^{**})].

*************

[frame="none",cols="^",valign="middle",grid="all"]

|===================

|pass:[

]

|*Click image to view desargues1.seg with KSEG.*

|

|===================

.Desargues Theorem.

*************

For △asciimath:[ABC] and △asciimath:[A'B'C'] and asciimath:[D=(A A')(B B')(C C')] we have that asciimath:[C^{**}=(A'B')(AB), B^{**}=(C'A')(CA)], and asciimath:[A^{**}=(B'C')(BC)] are collinear, i.e. asciimath:[(A^{**}B^{**}C^{**})].

*************

[frame="none",cols="^",valign="middle",grid="all"]

|===================

|pass:[ ]

|*Click image to view desargues2.seg with KSEG.*

|

|===================

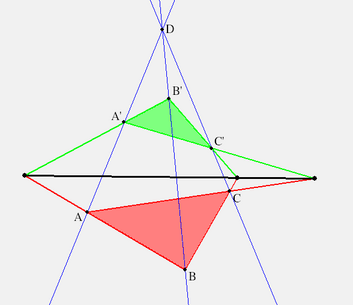

Now let's look at one ideal case, when both pass:[$ D \and A^** $]

are idea, i.e. pass:[$ (A'A) || (B'B) || (C'C) \and (BC) || (B'C') $].

[frame="none",cols="^",valign="middle",grid="all"]

|===================

|pass:[

]

|*Click image to view desargues2.seg with KSEG.*

|

|===================

Now let's look at one ideal case, when both pass:[$ D \and A^** $]

are idea, i.e. pass:[$ (A'A) || (B'B) || (C'C) \and (BC) || (B'C') $].

[frame="none",cols="^",valign="middle",grid="all"]

|===================

|pass:[ ]

|*Click image to view desargues3.seg with KSEG.*

|

|===================

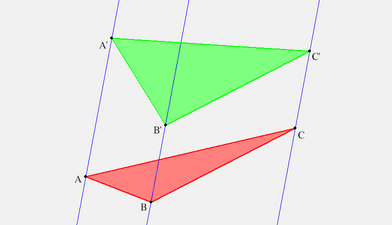

In this case, we have three parallal lines supporting the two triangles.

asciimath:[C^{**}=(A'B')(AB), B^{**}=(C'A')(CA)] are real (draw them !)

but asciimath:[A^{**}=(B'C')(BC)] is ideal. Now what does the conclusion of

Desargues' theorem, that asciimath:[(A^{**}B^{**}C^{**})]

is a line, mean in purely Euclidean terms?

It means that asciimath:[A^{**}] is on asciimath:[(B^{**}C^{**})],

i.e. that asciimath:[(B^{**}C^{**})] is a line parallel to

(both) asciimath:[(BC)] and asciimath:[(B'C')].

In other words, asciimath:[(B^{**}C^{**})] is in the pencil of

asciimath:[(BC)].

.Exercise.

======================

Easy: Give a similar description of the case that only pass:[$ D $] is ideal.

Challenging: What if only pass:[$ A $] is ideal?

======================

Next, let's play this game in reverse, and see what happens when ideal

points are made real. Here is a classical theorem about parallel lines

(see Tondeur, Chapter 1).

Pappus Theorem

--------------

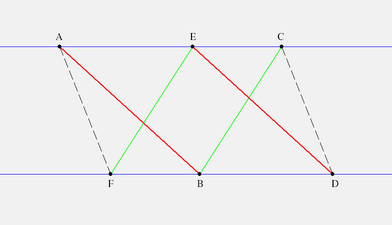

.Pappus Theorem.

*************

Let asciimath:[(ACE)] and asciimath:[(BDF)], and the two lines be parallel.

If asciimath:[(AB)\ ||\ (DE)] and asciimath:[(BC)\ ||\ (EF)] then asciimath:[(CD)\ ||\ (FA)].

*************

[frame="none",cols="^",valign="middle",grid="all"]

|===================

|pass:[

]

|*Click image to view desargues3.seg with KSEG.*

|

|===================

In this case, we have three parallal lines supporting the two triangles.

asciimath:[C^{**}=(A'B')(AB), B^{**}=(C'A')(CA)] are real (draw them !)

but asciimath:[A^{**}=(B'C')(BC)] is ideal. Now what does the conclusion of

Desargues' theorem, that asciimath:[(A^{**}B^{**}C^{**})]

is a line, mean in purely Euclidean terms?

It means that asciimath:[A^{**}] is on asciimath:[(B^{**}C^{**})],

i.e. that asciimath:[(B^{**}C^{**})] is a line parallel to

(both) asciimath:[(BC)] and asciimath:[(B'C')].

In other words, asciimath:[(B^{**}C^{**})] is in the pencil of

asciimath:[(BC)].

.Exercise.

======================

Easy: Give a similar description of the case that only pass:[$ D $] is ideal.

Challenging: What if only pass:[$ A $] is ideal?

======================

Next, let's play this game in reverse, and see what happens when ideal

points are made real. Here is a classical theorem about parallel lines

(see Tondeur, Chapter 1).

Pappus Theorem

--------------

.Pappus Theorem.

*************

Let asciimath:[(ACE)] and asciimath:[(BDF)], and the two lines be parallel.

If asciimath:[(AB)\ ||\ (DE)] and asciimath:[(BC)\ ||\ (EF)] then asciimath:[(CD)\ ||\ (FA)].

*************

[frame="none",cols="^",valign="middle",grid="all"]

|===================

|pass:[ ]

|*Click image to view pappus.seg with KSEG.*

|

|===================

.Question.

==================

Restate Pappus' theorem in Kepler's terms.

==================

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++

]

|*Click image to view pappus.seg with KSEG.*

|

|===================

.Question.

==================

Restate Pappus' theorem in Kepler's terms.

==================

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++

]

|*Click image to view hexagrmmum.seg with KSEG.*

|

|===================

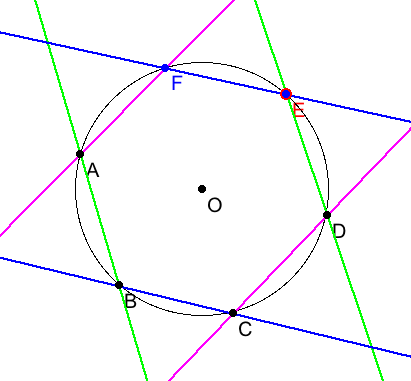

.Hexagrammum Mysticum

*************

If pass:[$ ABCDEF $] is a hexalateral inscribed in a 'conic section' then

pass:[$ G=(AB)(DE) $], pass:[$ H=(BC)(EF) $] and pass:[$ J=(CD)(FA) $] are

collinear.

*************

The circle is a well-known conic section, as are two crossing lines.

In Kepler's sense, two parallel lines are also qualify. They are a section

of a cylinder, and a cylinder is a cone with its vertex at infinity.

The intersections of the three pairs of opposite sides of a regular hexagon

are ideal, and hence collinear.

Inscribe a hexalateral in a circle, and see where these

three points are now? Don't be afraid to have sides of the polygon cross.

Move one vertex of the hexalateral off the circle and see what happens.

Finally, move all the vertices of the polygon off the circle, but carefully

perserving the collinearity you've observed. Any conjectures about where

these vertices must lie?

]

|*Click image to view hexagrmmum.seg with KSEG.*

|

|===================

.Hexagrammum Mysticum

*************

If pass:[$ ABCDEF $] is a hexalateral inscribed in a 'conic section' then

pass:[$ G=(AB)(DE) $], pass:[$ H=(BC)(EF) $] and pass:[$ J=(CD)(FA) $] are

collinear.

*************

The circle is a well-known conic section, as are two crossing lines.

In Kepler's sense, two parallel lines are also qualify. They are a section

of a cylinder, and a cylinder is a cone with its vertex at infinity.

The intersections of the three pairs of opposite sides of a regular hexagon

are ideal, and hence collinear.

Inscribe a hexalateral in a circle, and see where these

three points are now? Don't be afraid to have sides of the polygon cross.

Move one vertex of the hexalateral off the circle and see what happens.

Finally, move all the vertices of the polygon off the circle, but carefully

perserving the collinearity you've observed. Any conjectures about where

these vertices must lie?